Permanent Agriculture: A Holistic Approach to Sustainable Farm-Gardening

Permaculture, which comes from the union of “permanent” and “agriculture,” is a systems approach to agriculture aimed at mimicking the stability of ecosystems to produce inherently sustainable production. Often based on observations and principles of natural processes, permaculture aims to incorporate these processes in a sustainable farm garden environment. It’s a design philosophy akin to the Daoist principle wu wei, or more commonly in the Western tongue, “work smarter, not harder.” Here, harder doesn’t solely pertain to labor, but rather the microcosm of natural processes that we find in our particular gardening situations—work with nature, not against it. In his book Earth Insights, environmental philosopher J. Baird Callicott offers a great example:

One farms in a hilly region in which rains are plentiful but seasonally concentrated. One must irrigate one’s fields during dry spells in order to obtain a crop. A yu wei [opposite of wu-wei] approach would be laboriously to clear the uplands, which are more extensive, of timber, and plant one’s crops there. But since this will result in rapid runoff of rains and cause flooding of the narrow valleys, one also builds dams, at great cost of labor, both to control the floods and to impound the water for irrigation. To deliver the impounded water to one’s fields, one must carry or pump it uphill—also at great cost of labor or energy—to the high ground. While this style of agriculture may work for a while, and even yield large short-term profits, it cannot last long, because the soil will eventually wash off the unprotected hillsides, and the silt will settle behind the dams. A wu wei approach, on the other hand, would be to leave the forests on the highlands to hold the soil and plant one’s crops in the lowlands, diverting the steadily flowing streams to the planted fields by means of a series of ditches. One thus accomplishes the same general ends without all the backbreaking work and expenditure of energy. One’s short-term gains may be less, because one has put less land under cultivation, but they will be sustained indefinitely into the future.

How does all that translate to smaller-scale home agriculture? The twelve principles of permaculture give us some guidance:

- Observe and Interact: It’s helpful to watch the way nature conducts business so we can mirror its wisdom in our designs. Where water naturally collects after a storm is the perfect spot for a water feature or flood-tolerate plants instead of an area of derision.

- Catch and Store Energy: Activities like canning and drying may seem obvious, but other considerations are not. Planting trees near a house will catch the sun’s energy during harsh summer days. In the winter, the leafless branches allow sun to passively heat the home’s interior.

- Obtain a Yield: People need to eat. Regardless of other plans, the job of the farm garden is to produce food and harvesting when appropriate is key.

- Apply Self-Regulation and Accept Feedback: Sustainability implies Environmental Awareness. When designing for permaculture, do so in a way that observes the impact on local and global ecosystems. Also, view personal needs with modesty and take limitations in stride.

- Use and Value Renewable Resources and Services: Considering putting in a fence or border? A plastic one may last a long time (depending on its quality), but its manufacturing leaves a large environmental footprint. When it’s no longer useful, plastic ends up in the ever-mounting landfill. By contrast, wood is sustainable and biodegradable, while stone is freely available and will far outlast plastic.

- Produce No Waste: A fairly straightforward principle that could be applied to many aspects of life. Where sustainability is desired, waste has no place—permaculture observes practices that have recycling built right in.

- Design from Patterns to Details: Speaking of cycles, it’s easier to work from established patterns than going off the cuff at every turn. Once there is a reliable foundation in place, nuance can be added.

- Integrate Rather Than Segregate: This principle is aimed at the human aspect of agriculture and community. There is a place for everyone in such endeavors, and an inclusive attitude is golden.

- Use Small and Slow Solutions: Drastic responses to problems often lead to more problems. Managing issues with a patient and light touch is a better choice.

- Use and Value Diversity: One size doesn’t fit all. Having variety in the garden helps to fill different niches, prevents monoculture, and utilizes naturally-interdependent systems.

- Use Edges and Value the Marginal: Think outside the box and keep an open mind. Surprising, interesting things can be found if we look in unfamiliar or disregarded places.

- Creatively Use and Respond to Change: Change is an inevitable part of life. By responding to adversity in a positive and interesting way, a bust can be transformed into a boon.

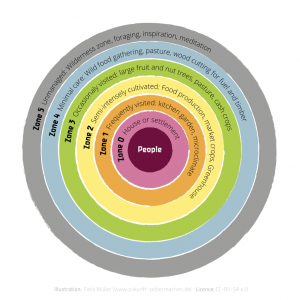

Another design principle of permaculture is layering. In the natural environment, one area can contain many levels of plants: tall tree canopies, midlevel shrubs, groundcover, etc. Reproducing this framework in a permaculture garden allows plants to work in unison rather than against the layout and against one another. Zones are also important. Dividing the garden into different zones based on their use is an efficient way to organize. It makes sense to keep the elements used most often close at hand. With this in mind, permaculture design places regularly tended crops like herb plants and soft fruits closer to the home, along with the worm compost bin for easy disposal of kitchen scraps. Moving outward, plants that require less attention, or are visited less frequently, are placed accordingly until a wilderness area is reached.

Overall, permaculture is less about hard-and-fast rules and more about an attitude of keeping the lessons of the earth in the forefront of farm garden design. It’s also not necessarily subsistence living, but many who adopt the design philosophy also take part in the self-sufficient lifestyle—one aspect lends itself to the other. This is only a cursory overview of permaculture; for more information on the design philosophy, please visit Permaculture Principles.