Microplastics: Stopping the Breakdown

Humans are critters for whom scale is an important concept. We tend to give a lot of consideration to things that are easily seen or heard, and minute variations are often missed by our radar. Spotting a discarded laundry detergent container or rogue plastic bags usually encourages an act of recycling, but what about all the smaller forms of plastics?

Humans are critters for whom scale is an important concept. We tend to give a lot of consideration to things that are easily seen or heard, and minute variations are often missed by our radar. Spotting a discarded laundry detergent container or rogue plastic bags usually encourages an act of recycling, but what about all the smaller forms of plastics?

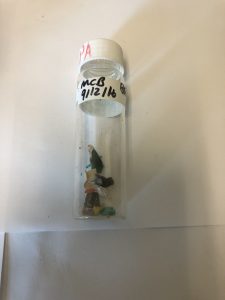

According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, microplastics are plastics of 5 millimeters or less in size. Unnervingly, they can be found everywhere: in soil, air, water, even ice cores in Antarctica. Microplastics are of two varieties: primary and secondary. Primary microplastics are those which are intended to be produced, typically as cosmetics and abrasives for industrial applications. You may be familiar with the former as they can be present in exfoliants and toothpastes, but legislation has sought to limit plastic in these products in favor of natural alternatives. Secondary microplastics are those that come from larger plastic commodities broken down by various processes—physical, biological, and photodegradation (sunlight). In the latter case, the pieces can be broken down to a size so small they are undetectable by the naked eye. This breakdown of plastic takes place all day, every day, all over the world, proliferating an immense number of tiny particles into the environment.

Microplastics are not only produced by weathering processes but also found in consumer goods. A study conducted in 2018 by State University of New York at Fredonia researchers found that 93% of bottled water from 11 different brands contained microplastic contamination—yet another reason to ditch bottled water. Unfortunately, simple, everyday necessities also produce microplastics, such as the microfibers shed from our clothes in the wash and the breakdown of vehicle tires.

Microplastics are not only produced by weathering processes but also found in consumer goods. A study conducted in 2018 by State University of New York at Fredonia researchers found that 93% of bottled water from 11 different brands contained microplastic contamination—yet another reason to ditch bottled water. Unfortunately, simple, everyday necessities also produce microplastics, such as the microfibers shed from our clothes in the wash and the breakdown of vehicle tires.

Our oceans are a repository for an inordinate amount of these microplastics (estimated at 270 thousand tons), and due to their small size, they are readily eaten by all kinds of organisms, from zooplankton to whales. Given that many marine animals are filter feeders, it’s easy to see why this is such a problem. Fish also ingest these plastics and can bring them right to our dinner table. And it’s not just the physical plastic itself that can disrupt organisms; the chemical compounds that make up microplastics move up the food chain too. More research still needs to be conducted to determine how this food-chain contamination affects human biology, but the affects of general microplastic chemical contamination are well-known. In next week’s article, we’ll take an in-depth look at how these microplastics and subsequent contamination affect our local Chesapeake watershed and coastal Virginia ecology.

Now that you’ve read that bummer of a tale, what can be done about it? For many of us, living a Rousseauin lifestyle out in nature is not a practical answer, but there are ways to mitigate our personal production of microplastics. As with many environmental issues, the answers are proactive rather than reactive: you don’t need to clean up what you don’t produce in the first place. This is of course the “reduce” part of the old “reduce, reuse, recycle” motto, but we can also add “refuse” to the beginning. By refusing single-use plastics when they are not needed and reducing the amount of plastics we acquire generally when alternatives are present (or refraining from purchasing some things all together), we negate the production and subsequent discarding of that plastic into the environment. Reusing is also key—no sense in throwing out or even recycling something that you can utilize instead of buying new. And regarding buying things, buying used is preferable. Technological solutions will need to be developed and implemented to clean up the microplastics that have already infiltrated our natural places. At our own individual level, we can apply “refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle,” enact lifestyle changes (anything from mindful consumerism to minimalism), and foster awareness of microplastics to stop the breakdown before it starts.

Now that you’ve read that bummer of a tale, what can be done about it? For many of us, living a Rousseauin lifestyle out in nature is not a practical answer, but there are ways to mitigate our personal production of microplastics. As with many environmental issues, the answers are proactive rather than reactive: you don’t need to clean up what you don’t produce in the first place. This is of course the “reduce” part of the old “reduce, reuse, recycle” motto, but we can also add “refuse” to the beginning. By refusing single-use plastics when they are not needed and reducing the amount of plastics we acquire generally when alternatives are present (or refraining from purchasing some things all together), we negate the production and subsequent discarding of that plastic into the environment. Reusing is also key—no sense in throwing out or even recycling something that you can utilize instead of buying new. And regarding buying things, buying used is preferable. Technological solutions will need to be developed and implemented to clean up the microplastics that have already infiltrated our natural places. At our own individual level, we can apply “refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle,” enact lifestyle changes (anything from mindful consumerism to minimalism), and foster awareness of microplastics to stop the breakdown before it starts.

Photos sourced from Wikimedia Commons