Victory Gardens: Food Gardens for Defense

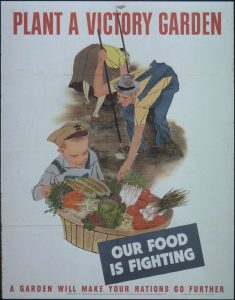

Victory gardens were born out of uncertainty and fear of the war. Citizens were encouraged to become more self-sufficient. Victory gardens were well-tended, productive vegetable gardens that would help offset the food demands of the military and the Lend-Lease program. Gardens were established in any arable soil like lawns, flower gardens, public parks, backyards, vacant lots and schools. There was some reluctance to engage in urban gardening because it was assumed city dwellers were not skilled gardeners and city sites could not support vegetable growth. That proved untrue and led to many cities producing mass amounts of crops.

Victory gardens were born out of uncertainty and fear of the war. Citizens were encouraged to become more self-sufficient. Victory gardens were well-tended, productive vegetable gardens that would help offset the food demands of the military and the Lend-Lease program. Gardens were established in any arable soil like lawns, flower gardens, public parks, backyards, vacant lots and schools. There was some reluctance to engage in urban gardening because it was assumed city dwellers were not skilled gardeners and city sites could not support vegetable growth. That proved untrue and led to many cities producing mass amounts of crops.

The ultimate goal of a victory garden was a continuous food supply throughout the seasons with emphasis on the importance of a garden plan, successive plantings and limited fertilization. Propaganda posters advocated that citizens “Sow the Seeds of Victory.” To maximize their garden’s production, home gardeners were encouraged to grow crops that were well understood, culturally adaptable, highly productive, widely grown and vitamin rich along with recording germination rates of seeds and disease and insects. Americans were advised to cultivate reliable crops for each season such as beans (pole, bush and lima), soybeans, cabbage, carrots, parsnips, winter squash, tomatoes, and various leafy vegetables like lettuce, chard, kale, beet greens and turnip greens which were valued more for their leafy shoots because there was more concern over vitamins than calories. Beans, (Phaseolus vulgaris) were valued for their high protein levels. Kidney, string, pinto, pea, navy and naricot cultivars were regularly grown. No edible plant got as much attention as the tomato (Solanium lycopersicum) as it was a considered a triple threat vegetable. First met with some hesitation as it is part of the poisonous nightshade family, tomatoes turned out to be rich in vitamins, easy to eat and feed children, along with being great for preservation and canning. Some cultivars that were grown were Beefsteak, Mariglobe and Jubilee. In order to grow early season vegetables that required warm soil, hotbeds were a means for extending the growing season. Hotbeds are small glass greenhouses that relied on microbial activity in manure and sunlight as heat sources. The goal was to keep the temperature at 65 degrees. Hotbeds were successful for tomatoes, peppers and eggplant.

The ultimate goal of a victory garden was a continuous food supply throughout the seasons with emphasis on the importance of a garden plan, successive plantings and limited fertilization. Propaganda posters advocated that citizens “Sow the Seeds of Victory.” To maximize their garden’s production, home gardeners were encouraged to grow crops that were well understood, culturally adaptable, highly productive, widely grown and vitamin rich along with recording germination rates of seeds and disease and insects. Americans were advised to cultivate reliable crops for each season such as beans (pole, bush and lima), soybeans, cabbage, carrots, parsnips, winter squash, tomatoes, and various leafy vegetables like lettuce, chard, kale, beet greens and turnip greens which were valued more for their leafy shoots because there was more concern over vitamins than calories. Beans, (Phaseolus vulgaris) were valued for their high protein levels. Kidney, string, pinto, pea, navy and naricot cultivars were regularly grown. No edible plant got as much attention as the tomato (Solanium lycopersicum) as it was a considered a triple threat vegetable. First met with some hesitation as it is part of the poisonous nightshade family, tomatoes turned out to be rich in vitamins, easy to eat and feed children, along with being great for preservation and canning. Some cultivars that were grown were Beefsteak, Mariglobe and Jubilee. In order to grow early season vegetables that required warm soil, hotbeds were a means for extending the growing season. Hotbeds are small glass greenhouses that relied on microbial activity in manure and sunlight as heat sources. The goal was to keep the temperature at 65 degrees. Hotbeds were successful for tomatoes, peppers and eggplant.

Home gardeners were also faced with the trial and error task of improving the soil to promote successful plant growth. They could encounter soils that ranged from rich loam in already established flower beds to compacted clay soils of vacant lots. It was recommended that manure and composted humus be added to the soil as amendments. Commercial fertilizer was to be used as a last resort for those without decayed manure or leaf-mold. Historically, guano and animal bones were used to provide nutrients to plants. Fertilizer shortages spurred creative thinking about nutrient recycling. Coastal areas used fish trimmings and algae, both rich in nitrogen as fertilizer. Sludge was also suggested to be dug into the garden soil, but it never achieved widespread use for fear of disease. In 1943, the Department of Agriculture and War Department approved a standard victory garden fertilizer with an N-P-K ration of 3-8-7. Nitrogen levels were lower than pre-war amounts because ammonia was needed for ammunitions. To combat insects and disease in gardens, commonly used insecticides and poisons like arsenic, nicotine and endosulfan were effective but potentially hazardous. A less potentially hazardous rat poison that could be grown was Red Squill (Drimia maritima). An onion relative, rats consumed it and died from the effects of the toxin scilliroside.

Home gardeners were also faced with the trial and error task of improving the soil to promote successful plant growth. They could encounter soils that ranged from rich loam in already established flower beds to compacted clay soils of vacant lots. It was recommended that manure and composted humus be added to the soil as amendments. Commercial fertilizer was to be used as a last resort for those without decayed manure or leaf-mold. Historically, guano and animal bones were used to provide nutrients to plants. Fertilizer shortages spurred creative thinking about nutrient recycling. Coastal areas used fish trimmings and algae, both rich in nitrogen as fertilizer. Sludge was also suggested to be dug into the garden soil, but it never achieved widespread use for fear of disease. In 1943, the Department of Agriculture and War Department approved a standard victory garden fertilizer with an N-P-K ration of 3-8-7. Nitrogen levels were lower than pre-war amounts because ammonia was needed for ammunitions. To combat insects and disease in gardens, commonly used insecticides and poisons like arsenic, nicotine and endosulfan were effective but potentially hazardous. A less potentially hazardous rat poison that could be grown was Red Squill (Drimia maritima). An onion relative, rats consumed it and died from the effects of the toxin scilliroside.

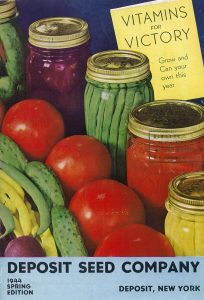

Harvesting and seed saving were also important parts of victory gardens. Harvest lent itself to preservation and specific vegetables were grown to last through winter. For example, tomatoes and beans could be canned while cabbage, carrots and winter squash could be stored for months. Food preservation involved several means such as root cellar storage, canning, drying, pickling and freezing. Canning was a home front activity for the duration of the war. It not only preserved food for later use, but it limited the metal and tin normally used, reduced food transport from farm to cannery and allowed more food to be used for military use. Seed catalogs featured vegetables, both fresh and preserved, accompanied by a patriotic message and cover design. Flowers like petunias, zinnias and marigolds were moved to the back cover. Home gardeners were urged to conserve seeds, sow moderately, avoid hoarding and to buy only the seed that was needed for a growing season. Careless buying and use of seeds was unpatriotic. A diversity of cultivars were offered for early, mid-season, and late varieties. Hybrid cultivars were relatively unknown so seed saving was a reliable way to prepare for next season. Beans, tomatoes, potatoes and melons were easy vegetables to collect seeds from. Due to the small plot of most backyard gardens—about 100 square feet—corn was not typically grown due to the lack of required space. By 1941, farmers in Illinois, Iowa and Indiana were growing hybrid corn, but seed had to be purchased for every season. If there was enough square footage, victory gardens may have grown a hybrid variety called ‘Bantam Evergreen’ which was a larger and later producing variety.

Harvesting and seed saving were also important parts of victory gardens. Harvest lent itself to preservation and specific vegetables were grown to last through winter. For example, tomatoes and beans could be canned while cabbage, carrots and winter squash could be stored for months. Food preservation involved several means such as root cellar storage, canning, drying, pickling and freezing. Canning was a home front activity for the duration of the war. It not only preserved food for later use, but it limited the metal and tin normally used, reduced food transport from farm to cannery and allowed more food to be used for military use. Seed catalogs featured vegetables, both fresh and preserved, accompanied by a patriotic message and cover design. Flowers like petunias, zinnias and marigolds were moved to the back cover. Home gardeners were urged to conserve seeds, sow moderately, avoid hoarding and to buy only the seed that was needed for a growing season. Careless buying and use of seeds was unpatriotic. A diversity of cultivars were offered for early, mid-season, and late varieties. Hybrid cultivars were relatively unknown so seed saving was a reliable way to prepare for next season. Beans, tomatoes, potatoes and melons were easy vegetables to collect seeds from. Due to the small plot of most backyard gardens—about 100 square feet—corn was not typically grown due to the lack of required space. By 1941, farmers in Illinois, Iowa and Indiana were growing hybrid corn, but seed had to be purchased for every season. If there was enough square footage, victory gardens may have grown a hybrid variety called ‘Bantam Evergreen’ which was a larger and later producing variety.

Victory gardens fulfilled myriad goals from fostering good nutrition and morale on the home front to reducing the need for agricultural crops so that they could be redirected to the military and the Lend-Lease program. Now is a great time to head back to our roots and start your own victory garden with heirloom seeds!

Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons